Walt Whitman on Thomas Paine

"The best and truest of men."

This testimony of the American poet Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892)) was taken down by Moncure Daniel Conway (1832-1907), the biographer and scholar of Thomas Paine. Even Whitman, the older of the two, was born too late to have known Paine, who died in 1809. But like Gilbert Vale, Paine’s earliest American biographer, he knew many of the people who had known Paine personally. In particular, Whitman mentions Col. John Fellows, Jr. (1759-1844). Fellows was a highly respected ships captain, graduate of Yale University, veteran of the Siege of Boston and the battle of Bunker Hill, author, and New York City bookseller who indeed knew Paine very well; they had roomed together and maintained a long and close friendship. Fellows was also a close associate of Gilbert Vale (1788-1866), the subject of my forthcoming biography.

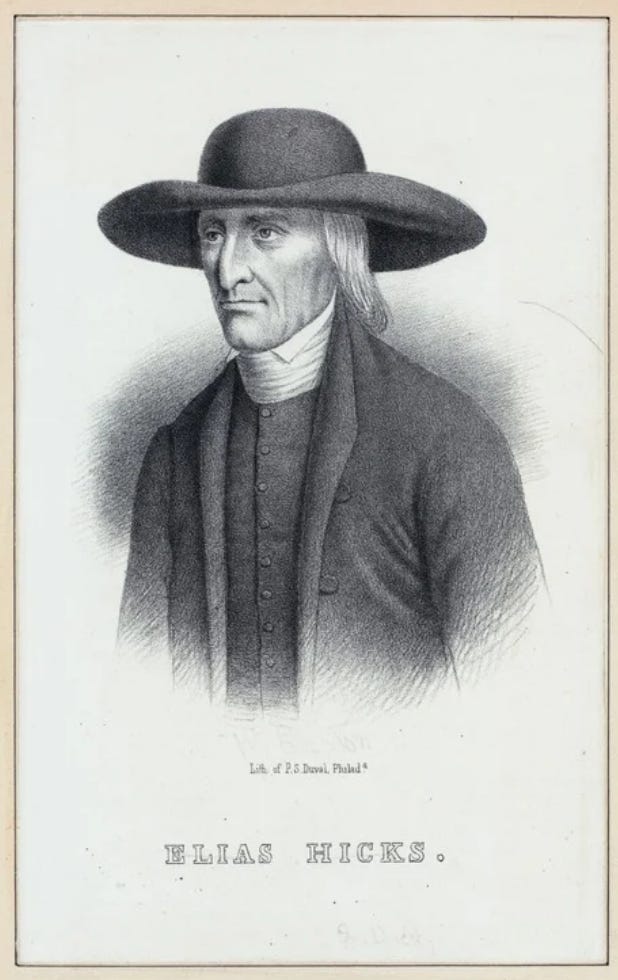

Elias Hicks (1748–1830), also mentioned by Whitman in the following text, was a Quaker leader and paripatetic (traveling) speaker who was a central figure in one of the greatest schisms in Quakerism and the founder of the Hicksite branch of Quakerism; perhaps the most original and basic of Quaker practices with no ministers and strict reliance on testimony of the “inner light” believed to reside in every person. His Quaker cousin, Willet Hicks (1765–1845), was a neighbor of Paine’s and visited him daily during the period prior to his death.

Here is Whitman on Thomas Paine and the others:

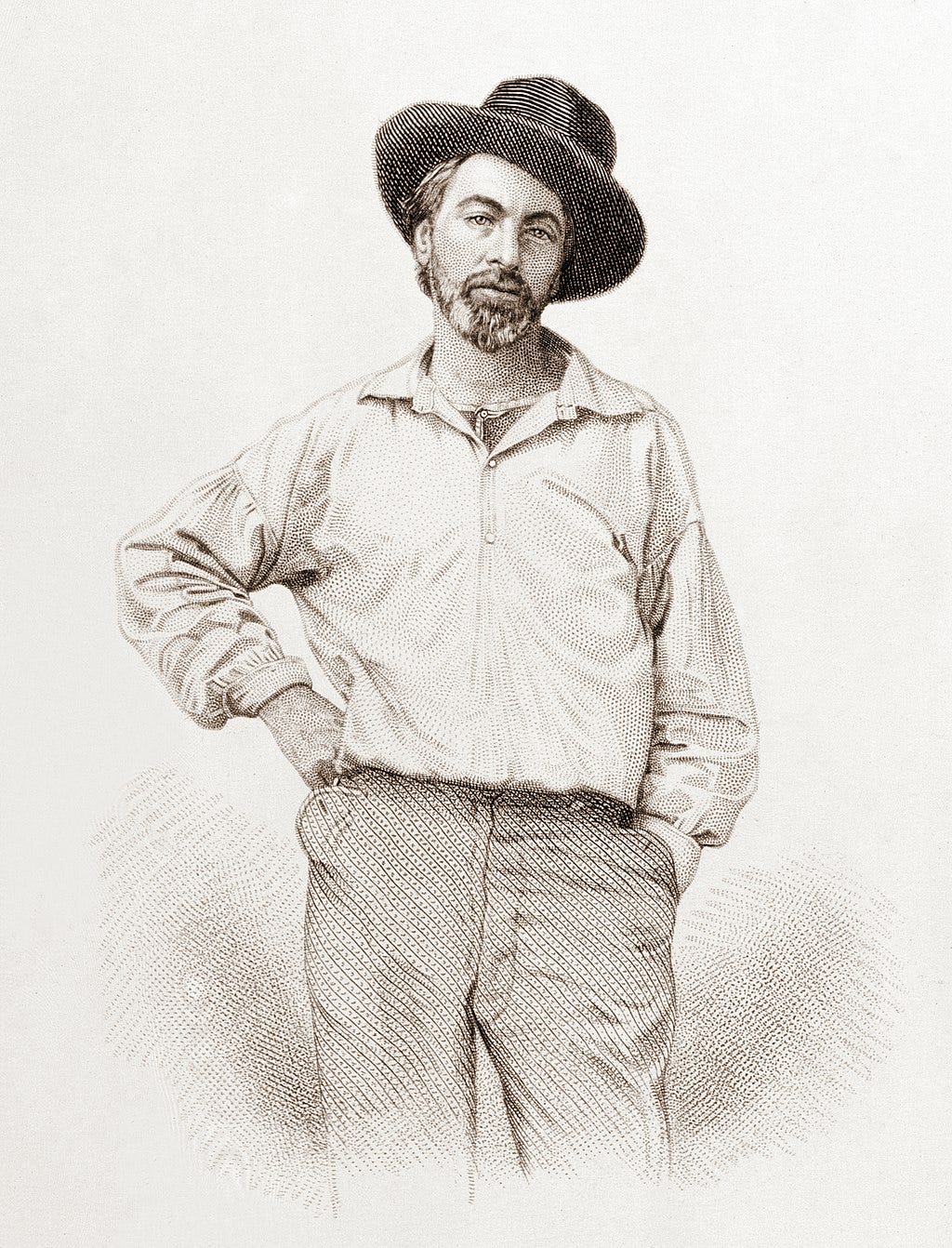

“In my childhood a great deal was said of Paine in our neighborhood, in Long Island. My father, Walter Whitman, was rather favorable to Paine. I remember hearing Elias Hicks preach; and his look, slender figure, earnestness, made an impression on me, though I was only about eleven. He died in 1830. He is well represented in the bust there, one of my treasures. I was a young man when I enjoyed the friendship of Col. Fellows, – then a constable of the courts; tall, with ruddy face, blue eyes, snowy hair, and a fine voice; neat in dress, an old-school gentleman, with a military air, who used to awe the crowd by his looks; they used to call him ‘Aristides.’ I used to chat with him in Tammany Hall. It was a time when, in religion, there was as yet no philosophical middle-ground; people were very strong on one side or the other; there was a good deal of lying, and the liars were often well paid for their work. Paine and his principles made the great issue. Paine was double-damnably lied about. Col. Fellows was a man of perfect truth and exactness; he assured me that the stories disparaging to Paine personally were quite false. Paine was neither drunken nor filthy; he drank as other people did, and was a high-minded gentleman. I incline to think you right in supposing a connection between the Paine excitement and the Hicksite movement. Paine left a deep, clear-cut impression on the public mind. Col. Fellows told me that while Paine was in New York he had a much larger following than was generally supposed. After his death a reaction in his favor appeared among many who had opposed him, and this reaction became exceedingly strong between 1820 and 1830, when the division among the Quakers developed. Probably William Cobbett’s conversion to Paine had something to do with it. Cobbett lived in the neighborhood of Elias Hicks, in Long Island, and probably knew him. Hicks was a fair-minded man, and no doubt read Paine’s books carefully and honestly. I am very glad you are writing The Life of [Thomas] Paine. Such a book has long been needed. Paine was among the best and truest of men.”

from

Conway, Moncure Daniel. The Life of Thomas Paine. New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1892. Vol. II, pp. 422-3.

***************************************Walt Whitman in 1855***********************************

Interesting, all the factions and lying, even in the days of our founders.