A review of:

Paine: Being a Fantastical Visual Biography of the Vilified Enlightenment Hero, by his Ardent Admirer ‘Polyp.’

Published by the author: © Paul Fitzgerald 2022, All Rights Reserved

Printed: Rap Spiderweb Ltd., Oldham (UK).

This pictorial narrative — author/illustrator Fitzgerald aka Polyp calls it “graphic history” — is illustrated with panache, imagination, and great creative talent. OK, they are cartoons. But just have a look at the images in this review.

The creation of this book began as a kickstarter.com campaign by the author who uses the handle “Polyp,” a cartoonist working in the UK. https://www.polyp.org.uk/ You can also find a Wikipedia article on him.

Full disclosure; after reading the pitch on Kickstarter and seeing some of the sample graphics, 21CR kicked in a small sum to further the project and contacted the author in hopes of steering him clear of some of the bigger pitfalls that always seem to re-emerge in the scholarship around Tom Paine. Polyp was cordial and cooperative, but without ever seeing more than a panel or two, the results of our efforts were limited.

If you envision reading the book on a 15 minute break, you will be mistaken; the pleasant surprise is that it is dense artistically and textually. At about 115 pages including explanatory material with approximately 166 colored images, most with multiple texts, there is content enough to wile away some pleasurable hours. It took me a little more than three days of spare-time reading to get through it. Your mileage may vary.

Artistically it is something between a fun-house and a comic time-capsule. The main thing to know about the graphic work is evident in the samples provided here. There really isn’t more to say except that the printers have done the artist justice with the saturation and crispness of the color images. It’s a great pleasure to look at. For the vegan and chemical averse, it’s printed with vegetable inks on paper carbon balanced at source. For info on carbon-balancing: https://carbonbalancedpaper.com/about/

On the history side of things, first a positive note; Polyp’s research is far ranging. The author drew from a wide variety of sources, many commonly overlooked, and from both enemies and supporters of Thomas Paine. His breadth of sourcing is admirable and shows a great deal of work. But bear in mind, these are secondary sources - not primary. That means that they must be treated with caution and often amount to opinion. What is the context? What agenda may the commentator have? This is a historical nuance absent from the text. It is as if the author tries to take all of them together, literally, and tries to cobble together a coherent tale. Whatever that may be, it’s not good history. The key narrators - some of whom will be unfamiliar to the casual reader - are introduced in the first pages.

Before offering some critical observations, I want to preface my comments by saying that I commend this effort and recommend it to those especially who love the medium; and to those for whom an uncharacteristic approach to history provides interest, inspiration, and entertainment. As with all interpretive narratives, however, the history student should bring a sharpened critical sense.

Examples abound:

U.S. President John Adams (1735 - 1826) has long been credited with the quote that "Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain." Polyp repeats it in this work [p.24], credits it to Adams, but gives no source. There is no source for the very good reason that Adams never said it nor can it be found in any of his writings. Some say that the earliest attribution to Adams was in about 1902, but it traces back a bit earlier. I have a document that credits it to Adams in about 1850. But there’s nothing earlier. Again, Adams neither wrote nor spoke it. There is, however, good evidence that the actual author was Joel Barlow (1754 —1812), American poet, diplomat, politician, and personal friend of Paine. The earliest appearance of the quote is in an unsigned introduction to a rare 1793 London edition of RIGHTS OF MAN. Adams played no part in the edition and it is known that Barlow did. If memory serves, it was John Adams himself who wrote that the introduction was said to have been written by Barlow. In any event it appears nowhere Adams’ writings or his speeches. Alert historians have attributed to Barlow for some time.

Fitzgerald repeats another long-debunked tale [p. 70]. This construction or fabrication — take your choice — is based on a letter from Benjamin Franklin to an unnamed recipient who had evidently presented Franklin with a work critical of Christianity and the Bible. Franklin recommended that his correspondent destroy the book. There are at least two problems with Polyp’s use. Here is the quote as he uses it:

”Think how great a proportion of mankind consists of weak and ignorant men and women who have need of the motives of religion to restrain them from vice. If men are so wicked as we now see them with religion, what would they be if without it?”

Polyp signs it “Benjamin Franklin.” The first problem is that Franklin never wrote it, at least not in this form. The original has been sliced and diced and large sections omitted. With apologies for the length, here is the actual quote in full with Fitzgerald’s excisions in boldface:

”I have read your Manuscript with some Attention. By the Arguments it contains against the Doctrine of a particular Providence, tho’ you allow a general Providence, you strike at the Foundation of all Religion: For without the Belief of a Providence that takes Cognizance of, guards and guides and may favour particular Persons, there is no Motive to Worship a Deity, to fear its Displeasure, or to pray for its Protection. I will not enter into any Discussion of your Principles, tho’ you seem to desire it; At present I shall only give you my Opinion that tho’ your Reasonings are subtle, and may prevail with some Readers, you will not succeed so as to change the general Sentiments of Mankind on that Subject, and the Consequence of printing this Piece will be a great deal of Odium drawn upon your self, Mischief to you and no Benefit to others. He that spits against the Wind, spits in his own Face. But were you to succeed, do you imagine any Good would be done by it? You yourself may find it easy to live a virtuous Life without the Assistance afforded by Religion; you having a clear Perception of the Advantages of Virtue and the Disadvantages of Vice, and possessing a Strength of Resolution sufficient to enable you to resist common Temptations. But think how great a Proportion of Mankind consists of weak and ignorant Men and Women, and of inexperienc’d and inconsiderate Youth of both Sexes, who have need of the Motives of Religion to restrain them from Vice, to support their Virtue, and retain them in the Practice of it till it becomes habitual, which is the great Point for its Security; And perhaps you are indebted to her originally that is to your Religious Education, for the Habits of Virtue upon which you now justly value yourself. You might easily display your excellent Talents of reasoning on a less hazardous Subject, and thereby obtain Rank with our most distinguish’d Authors. For among us, it is not necessary, as among the Hottentots that a Youth to be receiv’d into the Company of Men, should prove his Manhood by beating his Mother. I would advise you therefore not to attempt unchaining the Tyger, but to burn this Piece before it is seen by any other Person, whereby you will save yourself a great deal of Mortification from the Enemies it may raise against you, and perhaps a good deal of Regret and Repentance. If Men are so wicked as we now see them with Religion what would they be if without it?”

History, like science, draws its conclusions from the data. Providing no acknowledgment of the drastic textual omissions and rearrangements leaves the impression of trimming the narrative to fit a narrative, whether intentional or not.

The second problem is in the source of the quote itself and whether the letter was even addressed to Thomas Paine.

Franklin was indeed an important influence on Paine and readers may recall that it was Franklin who sent Paine to America and, in a sense, launched him in the direction of his famous career. And Paine of course wrote perhaps the most famous critique in history of the Bible and institutional religion, the Age of Reason, published in 1794. The Rev. William Wisner (1782–1871) was the first to claim that the Franklin “spit in the wind” letter was written to Paine. Wisner’s hit-piece was published as “Don’t Unchain the Tyger,” American Tract Society, 1833 — the flagship religious tract printer of the mass hysteria and revival movement later called the Second Great Awakening. The American writer and president of Harvard University, Jared Sparks (1789 – 1866), repeated the rumor and as with many a spicy tale, it proliferated wildly and for years to come. It is still repeated by evangelists and fundamentalists out to “get” Paine.

And once again, Mr. Fitzgerald has offered a quote that could not possibly have been written to Paine. Franklin died in 1790. Paine didn’t even begin to write Age of Reason until 1793. The letter is in fact unaddressed and the recipient anonymous, so the Paine attribution has never been more than an assumption snatched upon by his calumniators. MANY individuals and some Americans of the Enlightenment Period (c.1688 — 1789) wrote attacks on religion and the Bible, including Ethan Allen (1738 — 1789) although none as famous as Paine’s later writing. It could well have been written to Allen who published Reason the Only Oracle of Man ten years earlier in 1784.. Paine biographer Moncure Daniel Conway (1832 — 1907) noted Franklin’s observation that the anonymous recipient, unlike Paine, denied a “particular providence.” Stated in the affirmative, Paine warmly acknowledged a particular providence. Others have pointed out that Paine had already achieved international fame as a writer by the time Franklin would have had to write the letter. It is not an exaggeration to say that Paine was among the most famous authors in the world at that time. The letter, on the other hand, is plainly addressed to a person less consequential. Based on internal and external evidence, moreover, the most up-to-date scholarly collection of Franklin’s writings dates the letter to December 13, 1757 … long before Franklin met Paine in 1774. And yet, like an STD, this unsupported old slander pops up again and again. “Polyp” uncritically repeats it.

There are other problems. The author/illustrator quotes a great number of people who were known vilifiers and liars. To be sure, Polyp notes the adverse roles of SOME of them in his brief list of “Key Narrators” at the beginning of the book. He even divides the short bio summaries into “Friends and Advocates” and “Enemies and Vilifiers.” But he lists only the most major figures. Other equally compromised sources are quoted without qualifying explanation [see, for an example, Grant Thorburn, p. 90]. Common hearsay gets repeated without any qualification and as if it ought to be accepted alongside credible evidence [see Daniel and William Constable, pp. 89 and 91 or E. M Woodward, p. 84]. In the case of the Constable claim that “Carver says Paine drinks regularly a quart of brandy a day,” Carver later recanted saying that he and Paine had an argument and that he (Carver) had spoken and written in anger, asked Paine’s forgiveness, and wrote to Paine that he had never known a finer or greater man.

Another example of a pruned or re-purposed quote may be that of Georg Forster (1754 -- 1794). Polyp quotes him thus:

”His blazing red face dotted with purple blotches makes him ugly, although his eyes are full of fire.”

Even allowing for translation differences (Forster was German), the quote seems truncated against the following full translation:

“I found not much remarkable in him. Better enjoy him in his writings. What is eccentric and egotistical in some Englishmen, he has to the highest degree. His face is scarlet and full of purple spots, which make him ugly; apart from that, he has a spiritual physiognomy and a fiery eye” (letter of 17 May 1793).

If Georg Forster found him unremarkable, he may have been one of the very few. No mention of drinking. More importantly, was Forster’s May 1793 account of Paine’s appearance the result of the illness from which future President James Monroe (1817 — 1875) said he expected Paine would not recover? Perhaps what became the “abcess in the side” that nearly killed him and left him bedridden during the winter of 1794-95 was responsible for Paine’s blotchy complexion. Scholars Jeanette Mirsky and Allan Nevins [The World of Eli Whitney, NY: McMillan, 1952) believed that Paine may have had Parkinsons. We don’t know. Forster didn’t either. Neither does Polyp. But he jumps upon the old Federalist and evangelical/fundamentalist Christian band-wagon with gusto.

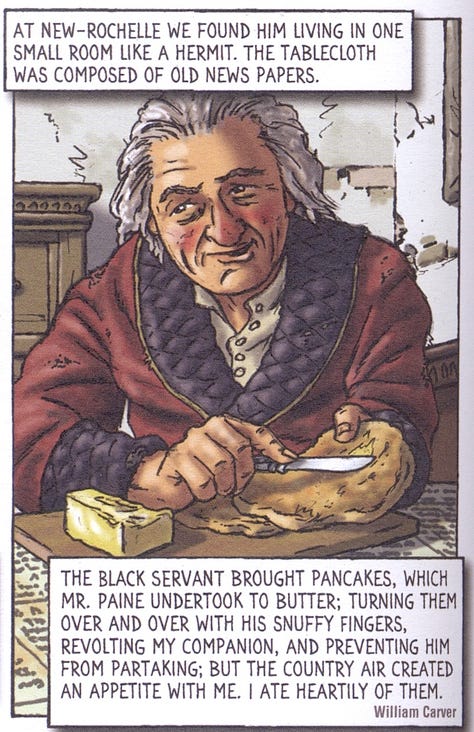

I’ve written about the subject of Paine’s purported alcoholism in the introduction to my six-volume collection of American responses to Paine [Thomas Paine in America, 1776 — 1809), London: Pickering Chatto, 2009]. The very few credible accounts of any excess of alcohol date from 1790 onwards when Paine was already 53 years of age and by far most of the claims were trotted about after he had written Age of Reason (1794), the work used by Federalists to attack Paine’s reputation. Perhaps Paine did drink a bit after watching virtually all of his revolutionary and philosophical brothers and compatriots guillotined, often outside the very cell in which he was imprisoned. Whatever he drank, it was the norm for a time in which water was not drunk at all — for very good reason — and far LESS than George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are well-documented to have consumed. Alcohol was nearly universal in the 18th century -- by the late 18th and early 19th century, teetotalling temperance advocates were horror-stricken by so much as a drop of demon-rum. The real question is why was Paine singled out then and now? And yet Polyp’s version of history depicts Paine as bloated, gin-blossomed, and drunk almost from the beginning of the book. I count at least twenty such caricatures, sometimes rather extreme. Clearly he had a lot of fun with this.

Above we have Paine back in England c. 1772 well before he even came to America, already something of a “wreck.”

Below a sampling of the “drunken” motif:

One more comment on the issue of Paine’s illness in later life. After his release from the Luxembourg Fortress, where he had narrowly escaped the guillotine, Paine was still, and without exaggeration, deathly ill. Then ambassador Monroe and his wife took Paine into their residence and did everything in their power to revive him. Monroe wrote (with Polyp’s excision again in bold):

”Mr. Paine has lived at my house for about ten months past. He was upon my arrival confined in the Luxembourg, and released on my application; after which, being ill, he has remained with me. For some time the prospect of his recovery was good; his malady being an abscess in his side, the consequence of a severe fever in the Luxembourg. Laterly his symptoms have become worse, and the prospect now is that he will not be able to hold out more than month or two at the furthest. I shall certainly pay the utmost attention to this gentleman, as he is one of those who merits in our Revolution were most distinguished.”

Another admirer and German translator of Paine’s works, C. F. Cramer (1752 — 1807), wrote to a friend of Paine suffering “incurably from the torture of an open wound in the side, which came from a decaying rib,” this latter quoted by Polyp.

What was the cause of Paine’s illness? The evidence is that he was plagued with it from sometime around 1790 until his death in 1809. Decaying rib? Fever from the Luxembourg? Appendicitis? Bright’s disease? Parkinson’s? Cancer? Author Craig Nelson thought rosacea (Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Nations. New York: Viking, 2006). We don’t know and probably never will. But in a time of medical ignorance and superstition, people of the period consistently misidentified illness.

How shocked should we be by these exaggerations and errors? Probably not very. Paul is a caricaturist and cartoonist; and a fine one. Paine was a great man and there is no reason to doubt that Polyp admires Paine. We have communicated on this topic and he tells me he believes the claims based on the testimony of Theobald Wolf Tone [1763 — 1798], whom he believes is a credible witness. Perhaps so. But again, Tone appears to have been in Paris with Paine for only part of 1797, the exact period in which Paine was struggling to recover from the illness that nearly killed him. So we have at best a brief snapshot; not much upon which to pillory a person’s memory.

In sum: brilliant illustrations, great story, often fun, but on balance it perpetuates and magnifies the campaign to denigrate Paine’s record and image. This is regrettable. Contemporary testimonies of Paine’s sobriety and probity — his radiating genius — vastly outnumber the comparatively rare and often demonstrably intentional efforts to stain his image and, by inference, elevate the accuser. Apart from the firmly documented political and religious assaults, how many others simply, and as is so common in human behavior, bad-mouthed Paine to elevate themselves at his expense? And yet, the “drunk motif” is repeated in this work with one lurid, mocking panel after another. Wouldn’t one have been enough? Two? Instead, the old calumny forms a substantial part of the graphic content and text.

The depth and complexity of the historical problems surrounding Paine are just hinted at in the somewhat unfortunate length of this review. No apology is, however, offered. Polyp’s efforts are admirable and his illustrative skills superb. Perhaps the medium of the graphic book is better suited for a simpler topic. If so, the author/illustrator is to be commended for his attempt. But if he intended — as he says — to present a balanced account, the effort fell short. The combined visual IMPACT upon the media-fixated attention-span of a good portion of Polyp’s audience, unfortunately, taints the work’s historical value.

Enjoy the illustrations, be extremely careful of the history — you’re welcome to inquire here for clarifications. North American purchasers can find copies here:

https://www.thomaspainesociety.org/product-page/paine-a-fantastical-visual-biography

or in Europe:

https://thomaspaineuk.wordpress.com/