In this case, it’s the late Thomas Fleming (July 5, 1927 – July 23, 2017), prominent historian and author of a long list of works both non-fiction and fiction, former president of the Society of American Historians, and the PEN American Center; the resumé is long and distinguished.

Anyone can make a mistake, but in this particular case it appears to be the outcome of a work in which Fleming wasted zero energy on any appearance of scholarly reserve. In THE GREAT DIVIDE: THE CONFLICT BETWEEN WASHINGTON AND JEFFERSON THAT DEFINED AMERICA, THEN AND NOW, Boston: Da Capo Press, 2015 Fleming is full of effusive admiration for Washington and Hamilton. And just as full of animus towards their contemporary opponents in what has come to be called the Anti-Federalist or Republican faction; Jefferson, Madison, and Thomas Paine among others. Any author can have an opinion, certainly. But no historian should wander from the demonstrable facts.

Case in point regarding Thomas Paine:

On page 147, Fleming discussed the Edict of Liberty of the revolutionary French Assembly that expressed its friendship and revolutionary solidarity with America by granting honorary French citizenship to Washington, Madison, Paine, Hamilton and many others [full list below]. Fleming went on to note that Washington and Hamilton did not respond and that “… Madision wrote an oozingly flattering reply, hailing the ‘sublime truths and precious sentiments of the revolution of France.’” And here followed the phrase with which we are concerned in this post.

Fleming wrote … “T. Paine, who had been banished from England, was in France and accepted the honor by joining the National Assembly in time to participate in the unanimous vote to extirpate royalty in France.”

This is false on a number of important and, one might wish, obvious points. Paine wasn’t banished from England; he fled with a arrest warrant for high treason and price on his head for writing possibly the single greatest political book of the entire period and arguably in history, RIGHTS OF MAN (1791). He did so with the king’s men in hot pursuit and escaped in a boat across the English Channel to France where he was received by cheering crowds. More importantly though, Paine was nominated from four departments as representative to the French National Assembly, accepted the seat of Pas-de-Calais, and risked his life to speak in the Assembly itself AGAINST the execution of the king. Nor was the vote of the Assembly for execution unanimous, as Fleming wrote; it was deeply divided 387 to 334. Paine voted to spare the life of the royals and suggested that Louis Capet (the former Louis XVI) be sent to America that he might learn the rights and duties of a free republican citizen. Fleming’s account is atrociously bad history. It turns history on its head. And it’s bad history made slander in the service of an author with a political and historical axe to grind.

I never knew Fleming. One wonders if he would have humbly corrected his errors and their attendant calumny. We’ll never know, but the many examples in his book lend doubt to the proposition. Reputation and acclaim don’t always equal high character or good history. Read critically, friends and colleagues; expecially when it comes to Thomas Paine. Many of the slanders leveled during his lifetime persist to our day, uncriticlly parroted by authors and historians who ought to know … and do … better.

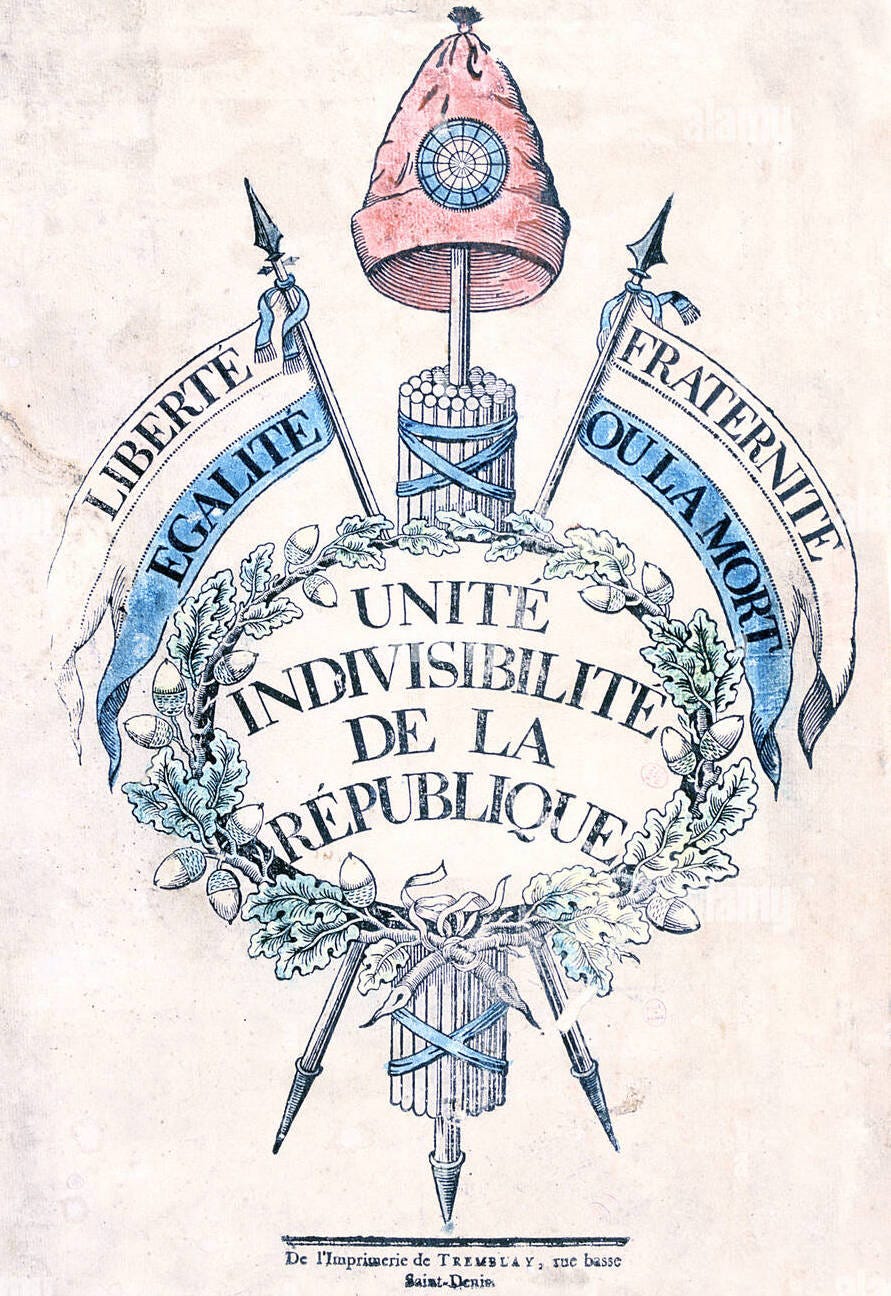

[Persons granted honorary French citizenship by the National Assembly in 1792: "men who, through their Writings and their Courage, have Served the Cause of liberty and prepared the freedom of the people." The individuals included (in the original spelling and order of the announcement): “Dr. Joseph Priestley, Thomas Payne, Jérémie Bentham, William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Jacques Mackintosh, David Williams, N. [Giuseppe] Gorani, Anacharsis Cloots, Corneille Pauw, Joachim-Henri Campe, N. [Johann Heinrich] Pestalozzi, Georges Washington, Jean [Alexander] Hamilton, N. [James] Maddisson, H. [Friedrich Gottlieb] Klopstock, and Thadées Kosinsko.”