A corporation is a financial instrument and a species of property. It may be owned by one or more humans [shareholders; sometimes but not always citizens of the country], but the corporation itself is a financial instrument created by law or legislation. While it is a financial instrument, however, a corporation has the same standing as you in a court of law or any other aspect of society and government. The judicial recognition of corporate “personhood” is a bit long for this format, but you can easily search it. Most scholars trace corporate “personhood” back to Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co. [1888] in which the railroad was recognized by the Supreme Court of the United States [SCOTUS] as having the same rights as an individual citizen under the 14th Amendment. Most readers will be aware that the more recent SCOTUS decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission [2010] expanded corporate rights by equating corporate money to individual speech. The result is that while you may only be able to spend a modest amount [$10 to $300] to support a candidate or cause you support, a corporation can and will spend millions or even billions if it so pleases. It becomes fairly obvious that speech, then, is no longer equal and neither is voting. If propaganda can sway minds, then corporations have more votes than you. And if they can purchase millions in ads, publcations, influence on newscasters, and legislators then that corporation has far more voting power than you do.

In light of this troublesome reality, some quotations from Thomas Paine’s work entitled Dissertation on First Principles of Government are presented as a sort of clarification or consideration of the state of the American republic - if indeed it is one - in light of corporate personhood and the role of property.

Don’t be deluded by the claim that “things have changed.” The first principles of government - as Paine called them - have not changed. Truth is still truth today as ever; perhaps more so than ever. It is people, our citizens, who are confused; not the principles themselves; and there can be no hope for reform or correction until we become crystal-clear on the underlying principles of government.

As always, your comments and observations are welcome. The quotes here are excerpted from the larger text and the citation itself is given below:

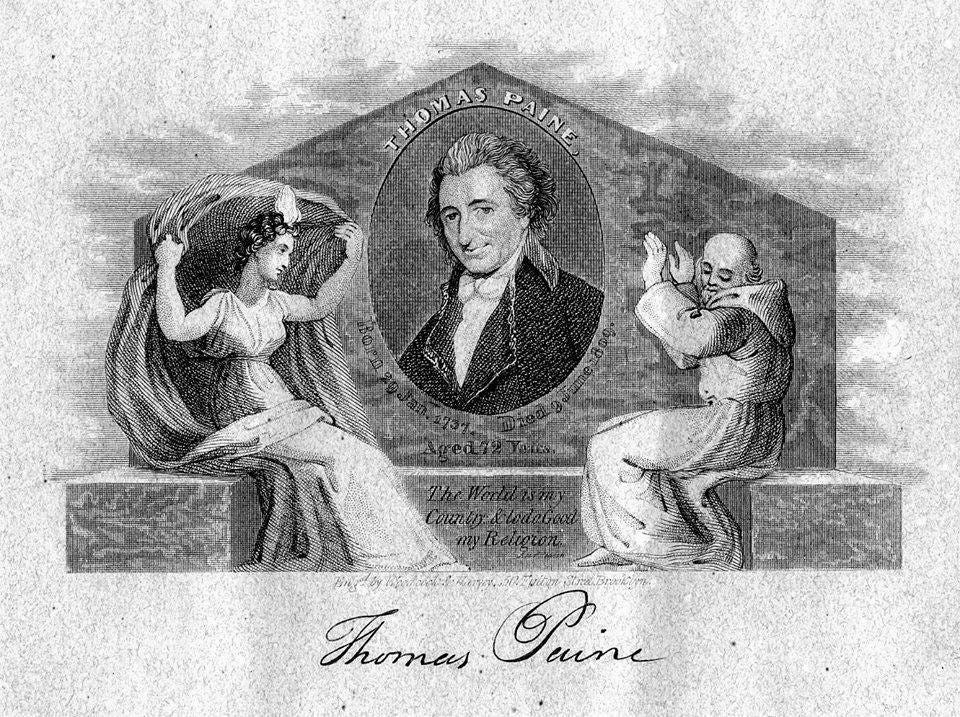

Thomas Paine

Dissertation on First Principles of Government

Paris: Printed at the English Press, 1794.

Personal rights, of which the right of voting for representatives is one, are a species of property of the most sacred kind: and he that would employ his pecuniary property, or presume upon the influence it gives him, to dispossess or rob another of his property of rights, uses that pecuniary property, as he would use fire-arms, and merits to have it taken from him

That property will ever be unequal is certain. Industry, superiority of talents, dexterity of management, extreme frugality, fortunate opportunities, or the opposite, or the mean of those things, will ever produce that effect without having recourse to the harsh ill sounding names of avarice, and oppression; and beside this, there are some men who, though they do not despise wealth, will not stoop to the drudgery or the means of acquiring it, nor will be troubled with the care of it, beyond their wants or their independence; whilst in others, there is an avidity to obtain it by every means not punishable; it makes the sole business of their lives, and they follow it as a religion. All that is required with respect to property is to obtain it honestly, and not employ it criminally; but it is always criminally employed, when it is made a criterion for exclusive rights.

I have always believed that the best security for property, be it much or little, is to remove from every part of the community, as far as can possibly be done, every cause of complaint, and every motive to violence: and this can only be done by an equality of rights. When rights are secure, property is secure in consequence. But when property is made a pretence for unequal or exclusive rights, it weakens the right to hold the property, and provokes indignation and tumult; for it is unnatural to believe that property can be secure under the guarantee of a society injured in its rights by the influence of that property.

As property honestly obtained, is best secured by an equality of Rights, so ill-gotten property depends for protection on a monopoly of rights. He who has robbed another of his property will next endeavour to disarm him of his rights, to secure that property; for when the robber becomes the legislator, he believes himself secure.

But if in the formation of a constitution, we depart from the principle of equal rights, or attempt any modification of it, we plunge into a labyrinth of difficulties from which there is no way out, but by retreating. Where are we to stop? Or by what principle are we to find out the point to stop at, that shall discriminate between men of the same country, part of whom shall be free, and the rest not? If property is to be made the criterion, it is a total departure from every moral principle of liberty, because it is attaching rights to mere matter, and making man the agent of that matter. It is moreover holding up property as an apple of discord, and not only exciting but justifying war against it; for I maintain the principle, that when property is used as an instrument to take away the rights of those who may happen not to possess property, it is used to an unlawful purpose, as fire-arms would be in a similar case.

The engraving above was commissioned by Gilbert Vale [1788-1866] for his biography of Paine published in 1841. It depicts a symbol of priesthood on the right, blinded by and rejecting the “light” of Thomas Paine’s great republican ideas and virtue; while on the left is liberty with her brow aflame and her cape billowing in Paine’s reflection. A facsimile of Paine’s signature is at bottom.